Visions of Wonderland

“And what is the use of a book,” asked Lewis Carroll’s Alice, moments before tumbling down the rabbit hole, “without pictures or conversations?”

— from “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”

Since its publication in 1865, more than 300 artists have created their own versions of the images and words in Alice’s eponymous adventure.

Many of those interpretations — including visions by painter Salvador Dali, printmaker Barry Moser, costume designer Irene Corey, Broadway composer Charles Strouse, pop-up book maker Robert Sabuda and the story’s original illustrator, John Tenniel — comprise Arizona State University Libraries’ assemblage of dozens of eclectic materials related to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and its sequel, “Through the Looking-Glass.”

The collection will be on display at the 10th annual Emeritus College Symposium on Nov. 7 in ASU’s Old Main building, which will celebrate the sesquicentennial of “Alice in Wonderland” by featuring a range of experts presenting on the breadth of Carroll’s influence. The event is open to the public.

Speakers include faculty associate Lou-ellen Finter’s photography of the American Southwest “through the Looking Glass”; astronomy and physics professor emeritus Per Aannestad on the connection between black holes and the Cheshire Cat’s grin; ASU Foundation CEO Rick Shangraw on “The Wonderland of ASU”; professor of supply chain management Craig Kirkwood on the digitization of the Alice books; and English professors emeriti Alleen Nilsen and Don Nilsen, who are compiling lists of the ways “Alice in Wonderland” was a zeitgeist in the 1960s and 1970s and continues to persist in popular culture.

“These books are so rich they offer so many opportunities for generating a wide variety of meanings,” said associate professor of English Dan Bivona, who taught Carroll’s books in his classes and is researching Alice’s relationship to Wonderland’s creatures in connection with the Turing test, which determines a machine’s ability to exhibit human behavior.

The mutability of the Alice stories is in part because of Carroll’s sparse text, which allows for creative interpretation. “If you don’t know what a Gryphon is, look at the picture,” he wrote in chapter nine, relying on the book’s illustrations to fill gaps in its text.

Each redesign has an effect on how the work is received, said art professor emeritus John Risseeuw.

Risseeuw spent 35 years teaching ASU students printmaking and the history of the book. He showed his classes the library’s different editions of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” to demonstrate varying approaches to illustrating the text or creating images to complement it.

An example he used was Carroll’s “Mouse’s Tale,” one of the first instances of concrete poetry, in which the visual nature of the text represents the concept that is written within — in this case, a long tale told by a mouse and printed in a winding, tail-like pattern. “The interesting thing is that in every edition of ‘Alice’ this has to be done by the typesetter, and it’s always done differently,” Risseeuw said.

Two versions of "Alice in Wonderland’s" long tale include a 1907 edition illustrated by Arthur Rackham and Barry Moser’s 1982 interpretation.

Nearly every edition of Alice in Wonderland — including many theatrical scripts — contains the tail tale.

Another commonality in many of the publications is their pictures’ resemblance to Tenniel’s originals.

“Tenniel is so good,” said Don Nilsen. “He did it so well. He captured the tone, and it was a very effective tone.”

Tenniel, the principal artist at the British weekly satire magazine Punch, spent more than a year perfecting his drawings for the book. His subtle inclusion of political allusions is often cited as a reason for Alice’s instant and enduring popularity among adult readers.

“What Tenniel did, in one way, is to make it so that people can never think about, say, the Mad Hatter, without imagining this guy without that big top hat,” Risseeuw said. “Whereas if you read the text without seeing that, your imagination makes up an image for the Mad Hatter. … So an illustrator actually takes something away from the reader — prevents their imagination from taking the story where they would imagine it and expand upon it, perhaps.”

Katherine Krzys, curator of the Child Drama Collection and archivist at ASU, recurrently found copies of Tenniel’s illustrations alongside directors’ designs for dramaturgical productions. “I was surprised at how much carryover there was between the different versions,” she said. “There’s a lot of Tenniel, but different interpretations of it.”

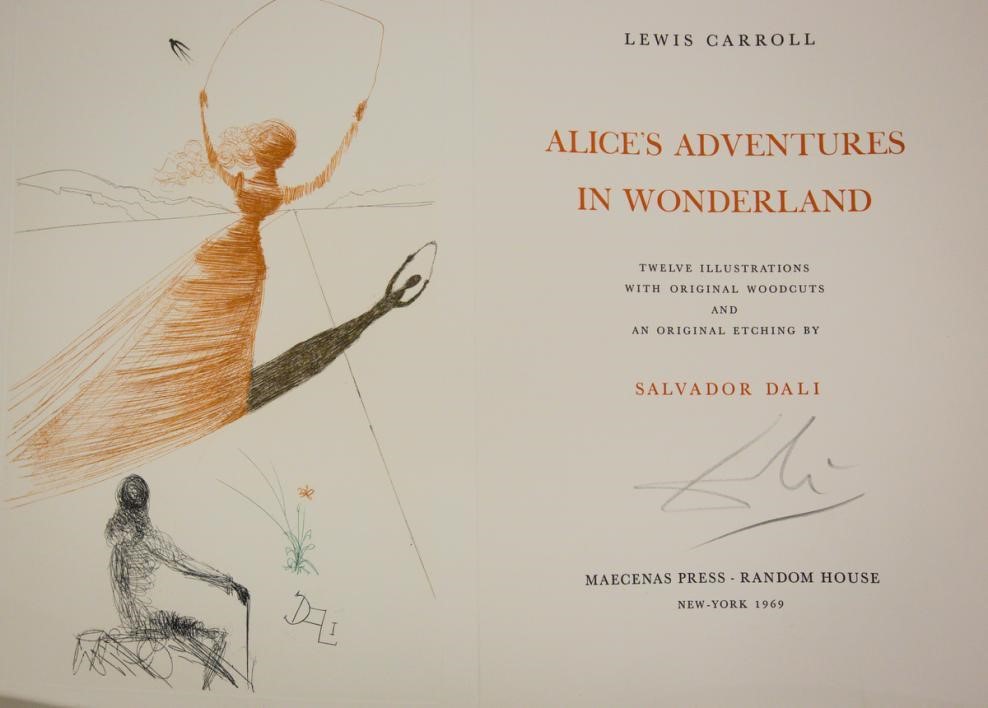

According to Risseeuw, part of the challenge for visual artists commissioned to portray Alice in a new way is to “put their own thing into it.” He points to Dali’s suggestive, semi-abstract visuals as a departure from the more traditionally definitive illustrations of Arthur Rackham, Peter Newell, Moser and others.

A Punch illustration published shortly after Carroll’s death proposes that those attempts fall short. The image, titled “Tenniel’s ‘Alice’ Reigns Supreme,” depicts newer versions of the White Rabbit and Alice paying homage to the original.

Undeterred, new copies are continuously issued, and a handful of 150th anniversary editions are being released this year.

“It’s all comparative,” Risseeuw said. “It isn’t that there’s one that stands out or that is better than the others. They’re all good by comparison to each other. They enrich each other.”

Hayden Library's Katherine Krzys talks about the costumes designed by Irene Corey for productions of Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland."

ASU’s special collections, including its editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, can be viewed in the Luhrs Reading Room during the school year from 9 to 6 p.m. on weekdays and by appointment on Saturdays. The reading room is located on the fourth floor of the Hayden Library, and a staff member is always available to help locate materials. ASU Libraries invites classroom visits and scholarly research. To learn more, contact 480-965-4932. Aspects of the exhibit can also be viewed here.