Embodying Empathy: Can Virtual Reality Make Us Better People?

When photographs appeared of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi’s body washed ashore on a Turkish beach, it “broke the heart of the world,” according to British television personality Jeremy Kyle. Internet searches for Syrian refugees spiked that day in September 2015 and have remained heightened since.

The stirring image fell in line with other icons of photojournalism that opened hearts and catalyzed social change.

Now, researchers are studying how virtual reality—which evokes sensory experience beyond the visual—can better capture the present and the past to improve how we relate to one another.

“We need to be able to think into other people’s situations and feel with them,” said Corine Schleif, professor of art history at Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. “Hopefully, we can get closer to those things with near total-immersion virtual reality so we can figure out what makes us tick, how we react to each other, how objects and other people are influential, and how we can live together within our environment.”

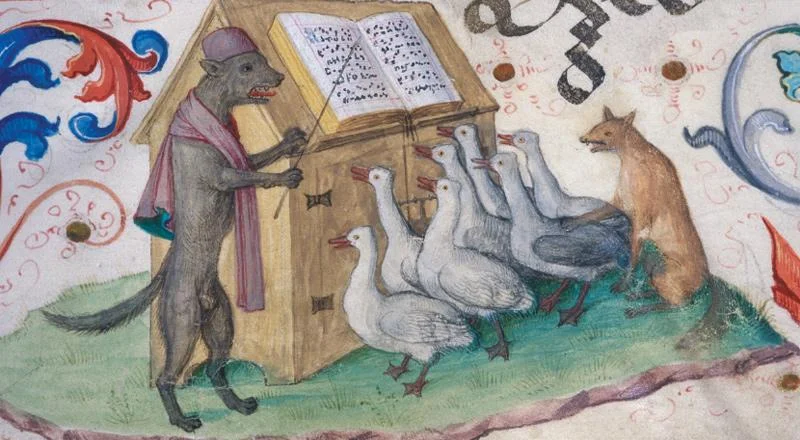

Schleif is leading a group of thirty international art historians, preservationists, theologians, musicologists, humanists, media designers, and acoustic engineers working to produce a multisensory reconstruction of a late-medieval Birgittine church.

The church, modeled after an original built in the fifteenth century at the Vadstena Abbey on Lake Vättern in Sweden, is the ideal object for virtual-reality study and experience, because it was conceived to stimulate the senses—it was filled with chants, layered textiles, arched spaces, and incense—and it played a central role in late-medieval life, says Schleif.

Immersing ourselves in what it was like to reside at the abbey and understanding why its inhabitants were a crucial part of the community and the roles they played in offering prayers and good works for those who lived outside its walls may open pathways to understanding how people relate in a universal sense.

The project, Extraordinary Sensescapes, is funded in part by ASU’s Institute for Humanities Research faculty fellows program, ASU President Michael M. Crow, and a grant from the Carnegie Humanities Investment Fund—private support on which it depends.

Now in the project’s early phases, scholars are collecting what’s left from the era to measure, study, and reproduce everything from the sound of songs reflecting from the church’s architecture, wall hangings, and vestments to what choir members saw when they looked down at hand-illustrated books of music or across a damp chamber filled with altars, candles, and sacred vessels.

Because the Vadstena Abbey acted as a motherhouse for monasteries of the Birgittine Order across Europe, scholars are able to gather details from objects belonging to disparate collections but representative of those found in Vadstena.

To their surprise, during a trip to the cloistered Altomünster Abbey outside Munich, they discovered a collection of rare manuscripts unknown to experts. The team is now trying to preserve the materials so they can be studied, publicly accessed, and incorporated into Extraordinary Sensescapes.

“It’s an additive process that will be built up digitally,” Schleif said of the process. “Ultimately, we can capture the past and actually feel what people were confronted with: what they saw, how they reacted to each other, and how their different emotions came together. We can use that as a kind of laboratory to ask questions about empathy.”

She says students react to virtual reality with “oohs” and “ahhs” in a “less consciously analytical and rather experiential” way. Viewers are impressed with the degree of reality that can be generated and how it enables them to explore a place—and the technology is expected to become more vivid, portable, and widely available.

For Schleif, the most valuable aspect of Extraordinary Sensescapes won’t come until it’s in users’ hands to analyze what they feel and think while embodying spaces that don’t exist elsewhere.

She asks: In what ways can sensory experiences generate emotion? What is appropriate and respectful to present? Whom does it help? Whom does it hurt?

She says students react to virtual reality with “oohs” and “ahhs” in a “less consciously analytical and rather experiential” way. Viewers are impressed with the degree of reality that can be generated and how it enables them to explore a place—and the technology is expected to become more vivid, portable, and widely available.

Out of the Cave and Onto the Screen

Scholars found the earliest known art painted on a cavern wall—the same setting Plato used to liken the unlearned to prisoners chained in a cave, unable to turn their heads so they only saw “virtual reality”: shadows projected on the wall that they confused for real life.

As technology enables art to more closely imitate life, we look at a handful of examples showing the evolution of representation:

Drawings: Sketches rose to commercial prominence when Renaissance artists, such as Michelangelo, included them in proposals to wealthy patrons to demonstrate—and help sell—yet-to-be-made paintings, sculptures, and buildings.

Art crticisim: The invention of movable type, etching, and woodcuts meant images could be reproduced and shared. In the eighteenth century, this led scholars to compare artworks—and the reality they conveyed—across regions.

Photography: The authenticity of photography dramatically changed observers’ capacity to empathize with the subjects depicted. In the late 1880s, magic lantern shows projected multiple images alongside live narration and music, one of the major precursors to movies.

Stereoscope: This 1838 device paired side-by-side images that, when viewed through attached lenses, fused the pictures in a single, three-dimensional scene. The View-Master, a special-format stereoscope, was made popular in the 1960s as a children’s toy and is now sold as a virtual-reality headset.

For Schleif, the most valuable aspect of Extraordinary Sensescapes won’t come until it’s in users’ hands to analyze what they feel and think while embodying spaces that don’t exist elsewhere.

She asks: In what ways can sensory experiences generate emotion? What is appropriate and respectful to present? Whom does it help? Whom does it hurt?

Perhaps most critical to the heartrending images we see in news today: What can it prevent?

“I really think that it’s all about here and now,” Schleif says. “It’s about what we can learn from those things in the past so we can make our world and our experiences better today—and not just better for a few people, but better for everybody.”